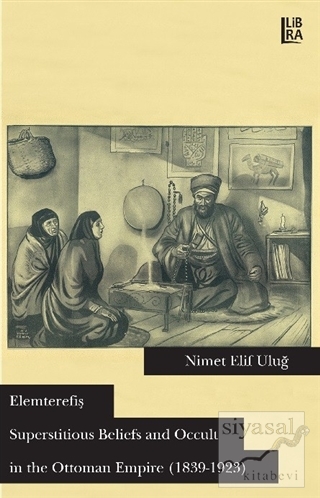

This book is about the social history of superstitious beliefs and especially magic and sorcery. I mainly tried to examine how superstitious beliefs and magic transformed the daily life of the Ottoman Empire into a world of superstitions in the nineteenth century. However, I had to go further back when I deepened my research into the origin of superstitious beliefs and magic seen in almost every period of the Ottoman Empire. I looked at polytheistic religions like shamanism, Animism, Manichaenism, Buddhism and Hinduism, which were the common religious beliefs of the former Turkish world. I included various other pagan religions and cultures underlying the past of the Ottoman geography over three continents as well as Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, the Sky God belief in Central Asia and finally Islam.

In the Ottoman Empire, “professional” magicians were of the ulema class who were not reluctant to utilize religious knowledge for their personal interests. In fact, they began to live immorally; “amateur” magicians were composed of occult groups, a.k.a. pseudo-clergy. I followed magic and magicians included in the documents of the Prime Ministry Ottoman State Archives only as they were caught as a result of a complaint. Füsun and Efsun, daughters of Cinci Arif Hoca, and their story add local and authentic flavor to the points made in the book.

This book is about the social history of superstitious beliefs and especially magic and sorcery. I mainly tried to examine how superstitious beliefs and magic transformed the daily life of the Ottoman Empire into a world of superstitions in the nineteenth century. However, I had to go further back when I deepened my research into the origin of superstitious beliefs and magic seen in almost every period of the Ottoman Empire. I looked at polytheistic religions like shamanism, Animism, Manichaenism, Buddhism and Hinduism, which were the common religious beliefs of the former Turkish world. I included various other pagan religions and cultures underlying the past of the Ottoman geography over three continents as well as Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, the Sky God belief in Central Asia and finally Islam.

In the Ottoman Empire, “professional” magicians were of the ulema class who were not reluctant to utilize religious knowledge for their personal interests. In fact, they began to live immorally; “amateur” magicians were composed of occult groups, a.k.a. pseudo-clergy. I followed magic and magicians included in the documents of the Prime Ministry Ottoman State Archives only as they were caught as a result of a complaint. Füsun and Efsun, daughters of Cinci Arif Hoca, and their story add local and authentic flavor to the points made in the book.