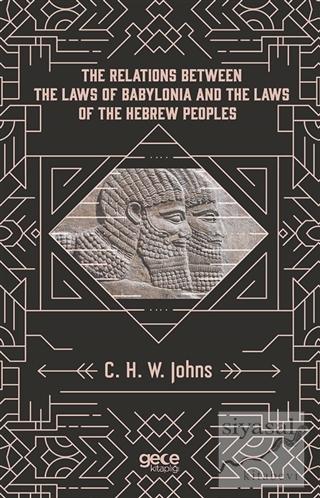

It has long been held that the laws of the Israelites, as revealed by God to Moses, by him embodied in the books of the Pentateuch and since preserved by the zealous care of the Jewish people, are incomparable. Accordingly they have been adopted professedly by most Christian nations and were early accepted by our own king Alfredas the basis of the law system of this our land.

We live in an age of devotion to comparative methods, when it is an article of faith to hold that the most fruitful means to attain a clear understanding of the exact nature of anything is to compare it with its like. This comparative method forms a large part of modern scientific research and, with proper safeguards and reserves, has become a favourite weapon of literary research into the history of human institutions.

Long ago, as it seems to us,Sir Henry Maineused itwhen he wrote hisHistory of Early Law. As a consequence of his investigations and those of many who have followed in his footsteps, the Science of Comparative Law has grown up. All the great law systems of the world have been classified and compared, and comparative lawyers felt qualified to assign to any new-found fragment of ancient law its true position in their schemes. The results had rather confirmed than traversed ancient claims for the supremacy of Mosaic Laws. Men had settled down to the belief that we might compare, and that to its great advantage, the Legislation of Moses with the Roman Laws of the XII Tables, with the Indian Laws of Manu or the Greek Code of Gortyna. We had recognized the broad outlines of a process of evolution and begun to understand the way in which, as a people advanced along the path of progress in the elements of civilization, similar human needs called forth similar solutions of the questions of right and wrong.

Nevertheless much remained obscure in many ancient legislations. It was the opinion ofJhering,the great authority on Roman Law, that for the ultimate solution of the puzzles of Roman Law we should have to go back to Babylon. In his days comparatively little was known about the laws of Babylonia, and that little was badly attested. Men were still of opinion that the Mosaic Law was the oldest of which we had any trustworthy account and that Babylonian laws, if there ever were any worthy of the name, must have been more barbarous and unformed.

It has long been held that the laws of the Israelites, as revealed by God to Moses, by him embodied in the books of the Pentateuch and since preserved by the zealous care of the Jewish people, are incomparable. Accordingly they have been adopted professedly by most Christian nations and were early accepted by our own king Alfredas the basis of the law system of this our land.

We live in an age of devotion to comparative methods, when it is an article of faith to hold that the most fruitful means to attain a clear understanding of the exact nature of anything is to compare it with its like. This comparative method forms a large part of modern scientific research and, with proper safeguards and reserves, has become a favourite weapon of literary research into the history of human institutions.

Long ago, as it seems to us,Sir Henry Maineused itwhen he wrote hisHistory of Early Law. As a consequence of his investigations and those of many who have followed in his footsteps, the Science of Comparative Law has grown up. All the great law systems of the world have been classified and compared, and comparative lawyers felt qualified to assign to any new-found fragment of ancient law its true position in their schemes. The results had rather confirmed than traversed ancient claims for the supremacy of Mosaic Laws. Men had settled down to the belief that we might compare, and that to its great advantage, the Legislation of Moses with the Roman Laws of the XII Tables, with the Indian Laws of Manu or the Greek Code of Gortyna. We had recognized the broad outlines of a process of evolution and begun to understand the way in which, as a people advanced along the path of progress in the elements of civilization, similar human needs called forth similar solutions of the questions of right and wrong.

Nevertheless much remained obscure in many ancient legislations. It was the opinion ofJhering,the great authority on Roman Law, that for the ultimate solution of the puzzles of Roman Law we should have to go back to Babylon. In his days comparatively little was known about the laws of Babylonia, and that little was badly attested. Men were still of opinion that the Mosaic Law was the oldest of which we had any trustworthy account and that Babylonian laws, if there ever were any worthy of the name, must have been more barbarous and unformed.